The HS2 of the Nineteenth Century

Power, politics and intrigue, the story of the 'little' North Western Railway

It was the HS2 of the Nineteenth Century. Designed to slash journey times between Yorkshire and Scotland. Its construction exposed an illegal sharing of revenue, secret pacts and caused the resignation of one of the most powerful industrialists in Britain.

How a forgotten railway in northern England, reshaped 19th century railway politics and for a while became a main line to Scotland.

The story of the 'little' North Western Railway.

At Settle Junction all eyes are focussed on the beginning of the famous Settle-Carlisle line. One of the wonders of Britain’s railway system, it passes through the dramatic scenery of the Yorkshire Dales and is rightly lauded as one of the great railway journeys in Britain, if not the world.

Easily overlooked amongst all this glamour and excitement, is the line that curves away westward at Settle Junction. Today, it is a half-forgotten route towards the fading seaside resort of Morecambe, but it was once poised to become the third main line route between England and Scotland. This is the 'little’ North Western.

A train coming off the 'little’ North Western at Settle Junction in 1986. The route towards Morecambe and the west coast can be seen curving away in the distance.

Photographer Stephen Houlker

During the 1850s the current east coast route was being developed by the Great Northern Railway. Its trunk route from King’s Cross to York via Peterborough was a serious threat to the established west coast route of the London & North Western Railway (LNWR). Mark Huish, the general manager of the LNWR, was a ruthless schemer whose central aim was to neutralise the Great Northern Railway’s Scottish ambitions.

The immense traffic likely to be generated by the forthcoming Great Exhibition focussed minds and in early 1851 the eight railway companies involved in Anglo-Scottish traffic signed what became known as the ‘Octuple Agreement’. It was a highly complex pooling of revenue. Huish was able to dictate the share of receipts and as a result the Great Northern Railway in particular could not draw the full benefits the east coast route should have brought them.

Huish was also seeking to restrict the rapidly expanding Midland Railway to the status of a provincial concern, as such they would merely feed passengers and goods into the LNWR’s trunk routes.

Amongst this swirl of railway politics the ‘little’ North Western Railway was trying to find partners to complete its line from Ingleton to Tebay, a line that would offer a direct link between Yorkshire and Glasgow and form a potential third Anglo-Scottish route. The engineering challenge of building the route was such that the ‘little’ North Western could not afford to complete it on its own. The obvious partner was the Lancaster & Carlisle Railway, a merger was proposed, but it was blocked by a number of Lancaster & Carlisle directors who were affiliated to the LNWR. The latter company was wary of facilitating a third Anglo-Scottish route that would become another competitor for the lucrative Anglo-Scottish traffic.

Another potential partner was the Midland Railway, who already operated services over the ‘little’ North Western to Lancaster and Morecambe. However, the Midland had entered into a secret, and illegal, common purse agreement with the LNWR after Parliament had blocked a merger between the two companies. Publicly, the close working relationship between the Midland and the LNWR was dubbed ‘the Euston Square Confederacy’. Therefore, the Midland were reluctant to enter into direct competition with the LNWR.

The increasingly frustrated ‘little’ North Western then made overtures to the last remaining railway with an interest in developing an Anglo-Scottish route, the Great Northern Railway. It set in train a series of events that would lead to the collapse of the Octuple Agreement and break the ‘Euston Square Confederacy’.

In 1856 the Great Northern put forward a Bill to Parliament that would see it construct the line between Ingleton and Tebay and seek running powers over the Midland Railway to Skipton, the ‘little’ North Western to Tebay and onwards over the Lancaster and Carlisle to Scotland. The new route would have been the shortest between Yorkshire and Glasgow by some sixty miles.

The LNWR, alarmed by the proposal, offered the Great Northern a fare pooling agreement in exchange for the dropping of the Bill. However, as the Bill was being heard, during a cross-examination session the secret ‘common purse’ agreement between the LNWR and the Midland was uncovered. The Midland had to rapidly, and publicly, abandon the common purse agreement. Additionally, the LNWR’s proposal to the Great Northern was leaked.

It turned railway politics on its head, as a direct result the Great Northern gained access to Manchester and, in a further twist of the knife, the Great Northern offered the Midland running powers into King’s Cross. The scheming of the LNWR was in ruins and in 1858 Huish resigned.

When the dust settled on the scandal, the Midland Railway strengthened its hand by taking over the ‘little’ North Western. In September 1861 the Ingleton-Tebay branch was completed and the ‘little’ North Western should have become the Midland’s route to Scotland.

Clapham, Yorkshire. This is where the now closed section of the ‘little’ North Western headed through Ingleton and towards the West Coast Main Line at Tebay

But the LNWR did everything in its power to make the operation unsuccessful. At first passengers had to detrain at Ingleton, walk across a viaduct and board another train. When through traffic did commence, Midland trains found themselves waiting for lengthy periods at Tebay to gain a path onto the west coast main line.

The stunning Low Gill viaduct on the now closed section of the ‘little’ North Western. You can purchase this wonderful image from the photographer Nina Claridge

The frustration forced the Midland Railway to plan its own route to Scotland, which would become the famous Settle-Carlisle railway. At the eleventh hour the LNWR backed down and offered the Midland a new agreement for traffic at Tebay; the Midland applied to Parliament to abandon the Settle-Carlisle line, but Parliament refused and forced the construction of the Settle-Carlisle.

Thus the Midland were compelled to construct the Settle-Carlisle, arguably the railway that no one wanted, but one which Parliament, driven by its dogmatic obsession with ‘competition’, insisted on being built.

In 1876 the Settle-Carlisle line opened to traffic and it became the third main route between England and Scotland. It relegated the ‘little’ North Western to secondary status. The line was closed to passengers in 1954, with the track being lifted in 1967. Today part of the line is used by the A65 road between Cowan Bridge and Ingleton. The viaducts at Ingleton, Sedbergh and Lowgill are protected by Grade II listed status, but the dramatic story of the line’s impact on nineteenth century railway politics has been almost completely forgotten.

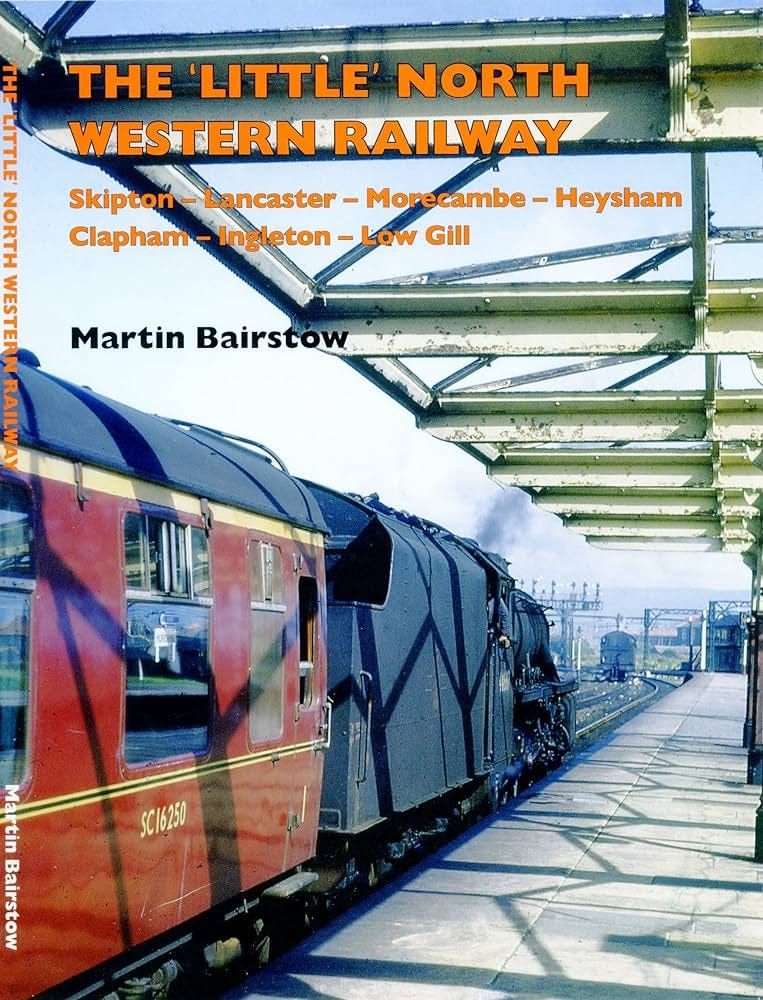

Further reading, Martin Bairstow’s fabulous book, The ‘Little’ North Western. The cover features a train awaiting departure from Morecambe Promenade station